Every Video Screen On the Planet...

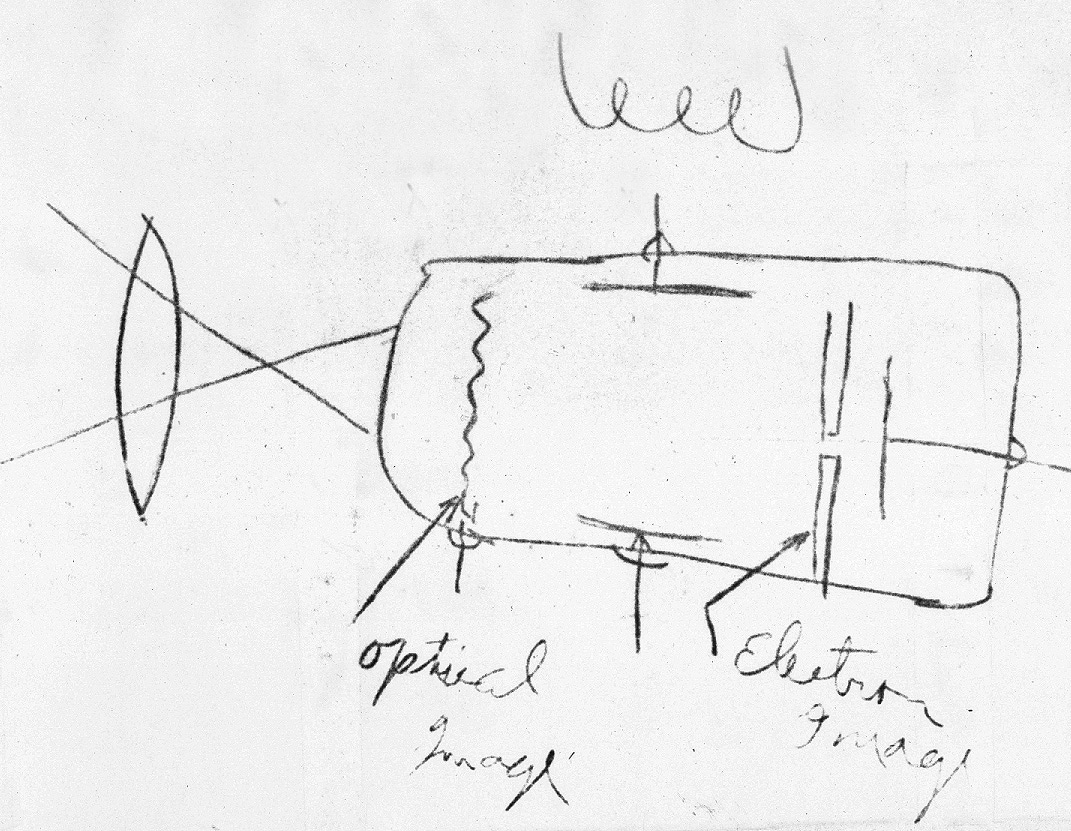

...Can trace its origins to this sketch...

(Consider this a preview of coming attractions. Approved for all audiences.)

What are you doing right now? You’re probably not conscious of the fact, it has become so second nature, so here’s a reminder: You’re staring at a screen.

Would you like to hear a story about that screen?

Step Into The Wayback Machine, Mr. Peabody

Stay with me now as we go back almost 100 years, to 202 Green Street at the foot of Telegraph Hill in San Francisco. There, during the evening of September 7, 1927 a 21-year-old prodigy from the Mormon frontiers of Utah and Idaho successfully tested the world’s first fully electronic television system. His name was Philo T. Farnsworth, and the rudimentary system he brought to life that night was built from scratch around an idea he’d come up with six years earlier — when he was only 14 years old.

But that’s not what I came to talk to you about today. If you want to know the rest of that story, I invite you to read a book.

Today, I want to talk about the convergence of video and computing. And I will attempt to make the case that much of the technology we take for granted today would not exist had it not been for what happened in that makeshift laboratory in San Francisco almost 100 years ago.

September 7, 1927 is the day that video arrived on this planet.

First, a bit of context:

I like to put it this way: September 7, 1927 is the day that video arrived on this planet. In the nearly 100 years since, the breakthrough unveiled that day has evolved to the point of… well, tell me again… what are you looking at?

A small circle of Farnsworth’s friends and family are ramping up now to observe the centennial of that event on September 7, 2027.

In 1977, we observed the 50th anniversary by gathering some of the still-living colleagues who’d helped Farnsworth build that first system and recreated it.

Here’s how that event was reported by the CBS Evening News:

I’d like to think we can do a something similar — but on a significantly grander scale — for the coming 100th anniversary.

To that end, I have begun compiling a “Countdown to the Centennial” in the form of “The Top 100 Milestones in the First 100 Years of Television” and/or video.

The task has turned into a bit of a monster, but will likely be my next book and should be the foundation of some kind of documentary retrospective of the first century of video. After 1927, the list includes such milestones as:

The first public demonstration of television in 1934

The broadcast of the 1936 Berlin Olympics

The first public TV service in the UK in 1936

The first ever television commercial — 15 seconds for Bulova watches — in 1941

The 1947 premieres of shows like Kraft Television Theater, Howdy Doody, and Meet The Press

The first Emmy Awards in 1949 (and how the award was, unwittingly, named after Farnsworth’s invention)

…and on an on. Each installment of the countdown is running ~900-1,000 words. My plan is to start the countdown on October 5th of this year and post one each week for the one hundred weeks leading up to the actual centennial in 2027. I’m shooting 100 arrows in the air — and the hope that they will land in a way that generates sufficient interest to make the centennial the global event it deserves to be.

A Lofty Premise

Central to this initiative, as stated at the top of this post, is the premise that “every video screen on the planet can trace its origins to the sketch that Farnsworth drew for his high school science teacher in 1922.” That sketch (which was introduced during patent litigation in the 1930s) illustrates the elegant idea he’d devised for converting moving images into a current of electricity. That nobody else came up with a similar idea (at least, none that would actually work…) is a testament to how far this kid was ahead of his competition in a race that had already been running for decades.

Other milestones in this list of 100 will explain how Farnsworth’s invention — and the patents he was granted starting in 1930 — laid the foundation for all the video technology on the planet today. One stop on that journey is the convergence of video with computing, which is in fact how most of us experience video today (see “what are you looking at?” above).

Number 73 in my Top 100 Countdown recounts the first time a cathode ray tube (aka “a television screen”) was used to see the output from a digital computer, MIT’s “Whirlwind.”

I am going to present that Milestone #73 here in its entirety. I invite anybody who reads this to try to shoot holes in the premise. Trust me, there are plenty of people who will find the premise preposterous, and I’m anxious to engage that debate.

So here is #73 in the Countdown of the Top 100 Milestones in the First 100 Years of Television (and video):

#73 — 1950 — Reaping The Whirlwind

With the work of John Logie Baird and others prior to 1927, the prehistory of video was electro-mechanical.1 Much the same can be said of computers.

Counting and calculating devices stretch back as far as recorded history.

The first known to use gears for calculating numbers was the Antikythera Mechanism, built sometime in the first century BCE and found in a shipwreck off the Greek Island of Antikythera in 1901.2

The modern quest for mechanized calculating began in earnest in 1642, when French mathematician Blaise Pascal developed the Pascaline, the first machine to use gears to perform addition and subtraction. In 1801, another Frenchman, Joseph-Marie Jacquard, devised a system that used punch cards that transformed the common textile loom into a programmable machine — arguably laying the conceptual groundwork for modern computing.

And in 1837, the English polymath Charles Babbage designed and built the "Difference Engine" — a fully mechanical, general-purpose computing device with components resembling a modern CPU and memory.

Enter Electricity

Electricity came to calculating in 1890, when American inventor Herman Hollerith built the Tabulator, which used punch cards and electric circuits to process the U.S. Census.3

At Bletchley Park outside of London during World War II, British mathematician Alan Turing led the top-secret development of the Bombe, an electro-mechanical device that helped crack the Nazi Enigma code, a pivotal turning point in the Allies' final victory.

And in 1945, physicist John W. Mauchly and engineer J. Presper Eckeret at the University of Pennsylvania built the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC) — the first fully electronic, general-purpose programmable computer. ENIAC used 18,000 vacuum tubes, weighed 30 tons and filled an entire room, but could complete in seconds calculations that previously took hours or days.

Add a CRT

But what we think of as a computer today didn't take shape until somebody had the bright idea to attach a cathode ray tube to an electronic computing machine. That did not happen until middle of the 20th century.

In 1950, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) unveiled "Whirlwind," the first digital computer capable of real-time processing. Originally commissioned by the U.S. Navy to simulate flight dynamics for pilot training, Whirlwind evolved into something far more ambitious—a high-speed, general-purpose computer that could process and respond to data as it was input, rather than executing one batch job at a time.

At MIT, Jay Forrester (Project Director), Robert Everett (Chief Engineer), Charlie Adams, David Sayre, and a rotating crew of engineers and technicians pioneered the use of cathode ray tubes (CRTs) to display digital data as it was output. They repurposed a surplus radar display and developed digital-to-analog conversion circuits that enabled the system to render computer-generated graphics directly onto the screen — thus creating the first real-time computer interface.

With the addition of the CRT, the MIT team could see results as they were calculated. The CRT turned the computer from a static calculating engine into a dynamic system, a concept that would become central to every digital device to follow, from radar consoles to video games, personal computers, and, well… whatever you’re gazing at now.

The first integration of video and computing technology in 1950 raises an interesting question: if electronic television had not been invented in the 1920s and developed through the 1930s and ’40s, would cathode ray tubes (CRTs) have been refined enough to serve as a computer display?

The answer, quite plausibly, is no.

Starting with the sketch that teenaged Philo Farnsworth drew on a chalkboard in Rigby, Idaho in 1922, CRTs were shaped by the demands of television4. Absent the Image Dissector camera tube that Farnsworth successfully tested in 1927, there would have been no electronic signal, no picture tube and no high-resolution display.

Once the concept was proven, the push was on to improve scanning methods, image resolution, phosphor sensitivity, and screen brightness. All the improvements introduced in the 1930s — not the least Farnsworth's own 100-plus patents — started on his workbench in San Francisco.

Without the engine of broadcast television pulling the train, without networks, advertisers and viewers all clamoring for brighter, sharper images, the CRT would never have achieved the resolution required for graphical computing. And none of that would have been possible without the electronic camera that produced a high resolution video signal in the first place.

The cathode ray tube that found its way into millions of living rooms in the 1950s became the default display for digital data during the same period. The CRT became a viable computer display not because computing demanded it, but because television made it possible. Starting with MIT's Whirlwind, the evolution of graphical interfaces depended on video technology that owes its existence to Farnsworth's first patent.

From the Antikythera to the iPhone, from radar systems to video games, the now common, daily routine of modern computing — click click, look look — was first made possible by the scan lines meant for sitcoms, variety hours, and the evening news.5

So it is no exaggeration to say that every video screen on the planet can trace its origins to the sketch that Philo Farnsworth drew for his high school science teacher in 1922.

That is the case we hope to have firmly established in time for the Centennial in 2027.

1 If you're not recognizing the name of John Logie Baird, follow the link; that will be covered in #96 of the Top 100 Countdown.

2 If the reference here sounds vaguely familiar, that might be because you saw the 2023 film Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. The object of Indie's quest in that movie was called "Archimedes’ Dial" and was loosely based on Antikythera Mechanism. The gadget in the movie is professed to have time travel powers, but the real artifact was an ancient Greek device for predicting astronomical events.

3 In 1896, Herman Hollerith formed the Tabulating Machine Company, which would eventually merge with others to become International Business Machines (IBM) in 1924. Hollerith’s use of punched cards directly influenced early computer data storage and programming methods.

4 The cathode ray tube (CRT) went through several stages of evolution in the late 19th century before its first use in television:

Johann Wilhelm Hittorf (1869) — discovered “cathode rays," streams of electrons moving through a vacuum;

Sir William Crookes (1870s) — built the Crookes tube, an early vacuum tube that visibly demonstrated the properties of cathode rays;

Karl Ferdinand Braun (1897) — invented the first oscilloscope-style CRT—a vacuum tube with a fluorescent screen used to display electrical waveforms, often considered the first practical CRT.

The idea of using CRTs for television gained traction in the early 20th century. British scientist A.A. Campbell Swinton proposed a fully electronic system in a letter published in Nature magazine in June 1908; Around the same time, Russian Boris Rosing developed a hybrid system using a mechanical camera and a CRT display, becoming the first to use a CRT to display a moving image. Rosing's experiments were observed by a student named Vladimir K. Zworykin, who applied for a U.S. patent for a similar system in 1923 after immigrating in 1921.

Philo Farnsworth may have had knowledge of either Swinton's proposal or Rosing's experiments, but the receiving end of the television equation was always going to be the easy part. With his Image Dissector - first successfully demonstrated in 1927 — Farnsworth was indisputably the first to come up with a fully electronic video camera.

5 Thanks to CBS Sunday Morning host Charles Osgood, who coined the phrase "click click, look look" to describe his first experience of 'writing' on a word processor.

I distinctly remember looking at the back of the TV when I was about 3 yrs old and trying to figure out how all the things I watched could fit into the TV. And what did they do when the TV was off? I also remember bargaining with my mother: I could watch Robin Hood if learned to tie my shoes. With that incentive, I learned it in about 3 minutes ;-)!