First, let's state the obvious: you have to be of a certain age to even understand the question.

You have to be old enough to remember the first television sets, with their rabbit ear antennae, bulbous cathode ray tube receivers and a dial that had only twelve channels, 2 through 13.

If you remember any of that, then you're old enough to wonder why there was no Channel 1. And if you’re not that old, then good for you, being curious enough to continue reading.

The story is worth telling because it's a timely reminder of how we got a world where virtually every aspect of our lives is controlled by some corporate monolith.

The monolith in this case was called the Radio Corporation of America.

You may have to be of a certain age to remember that, too, since the once great RCA is essentially no longer a going concern. It was acquired in 1986 by General Electric. That merger poetically reversed the process that began during World War I, when the Wilson administration persuaded GE to acquire the the assets of British-owned American Marconi and spin them off into a new American company, The Radio Corporation.

But we are not going into those monopoly origins today. Rather, to understand the disappearance of Channel 1, we are going to talk about arcane things like radio spectrum space and patent litigation. And we're going to peer into the ruthless rivalry between two titans of early radio: David Sarnoff and Edwin Amrstrong.

Sarnoff's name might be familiar, since history is always written by the victors.

Armstrong is the vanquished genius.

In the 1930s, Edwin Armstrong invented an entirely new kind of radio. And all the thanks he got was protracted industrial warfare with David Sarnoff and RCA over the new tech’s adoption. Channel 1 was part of the collateral damage.

Lesson 1: AM -v- FM

In the 1930s, much was at stake in the wild frontier of the electromagnetic spectrum – that invisible realm where radio signals travel. But radio technology was already getting long in the tooth, and it was also clear that audio-only would soon be displaced by the addition of pictures – television.

Edwin Armstrong is arguably the inventor of what we now think of as radio. Yes, Marconi and Tesla were among the first to successfully modulate radio waves in order to transmit information through the ether. But Armstrong invented two critical circuits that made radio the household fixture that it became in the 1920s and 30s.

Armstrong’s 'regenerative feedback' circuit provided amplification; the 'superheterodyne' circuit provided tuning. With the addition of those circuits, radio went from cats-whiskers-and-headphones to furniture with loudspeakers and a dial. All those Depression era photos of families staring at their radios? You can thank Edwin Armstrong for that.

Armstrong sold his patents to the Radio Corporation of America in 1920, just a year after the company was formed, adding considerable heft to the new company’s mission "to collect patent royalties, not pay them." Every company in the United States (if not the world) that manufactured radio equipment paid a license fee to RCA for the privilege. In return for the sale of his patents, Armstrong became RCA's largest individual stockholder and a close friend of the company's ascendant executive, David Sarnoff.

Sarnoff and Armstrong spent long nights in Sarnoff's personal radio room, tuning in signals from all over the world. One night in the late 1920s, Sarnoff expressed his frustration with the atmospheric interference that marred the reception, and wished aloud that "somebody could invent a little black box that would eliminate all the static” that plagued radio of the era.

The consensus at the time was that no such black box was possible, that static was forever. But Armstrong – who had done more to advance the art of radio than anybody since Marconi – considered it a challenge.

Several years later, Armstrong introduced his solution, but it was much, much more than a little black box. It was an entirely new kind of radio.

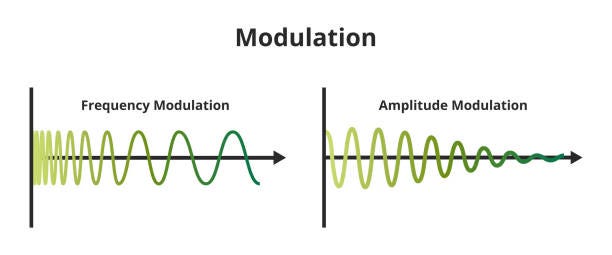

A radio wave has two primary elements: its amplitude (the height of the wave) and its frequency (how many waves per unit of time). In its first incarnation, radio employed "Amplitude Modulation" – AM – to piggyback sound on a radio wave by fluctuating in the amplitude of the wave.

In 1935, Armstrong demonstrated an entirely new way of transmitting radio signals. Rather than modifying the amplitude of the wave, Armstrong invented a way of modifying the frequency of the wave, thus introducing "Frequency Modulation" – FM.

Those who witnessed the first demonstrations of FM were stunned to hear crystal clear audio, entirely free of static, hiss, hum and crackle. Both music and speech came through as if they were being heard live – an extraordinary achievement in 1935.

There was just one problem: With the advent of FM, all the radio equipment in the world was suddenly obsolete. Rather than being the welcome 'black box' solution that he had longed for, the advent of FM presented a world of hurt for David Sarnoff and RCA.

Lesson #2: Bandwidth Allocation

By now you're probably wondering "what does any of this have to do with the disappearance of Channel 1? Bear with me. First I have to explain bandwidth and how it is allocated.

Bandwidth is a range of frequencies on the electromagnetic spectrum, typically measured in Hertz (Hz)1. To maintain order across the spectrum, regulatory bodies like the FCC in the U.S. assign specific frequency ranges to services like radio, TV, cellular, civilian or military use.

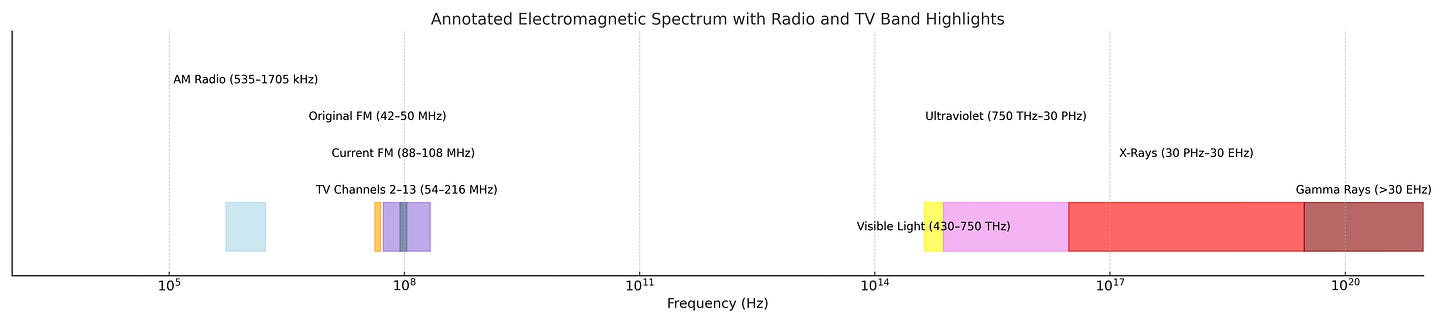

AM radio occupies frequencies between 535–1705 KHz. Slices of that bandwidth are assigned to stations around the country so that their signals will not overlap or interfere with one another.

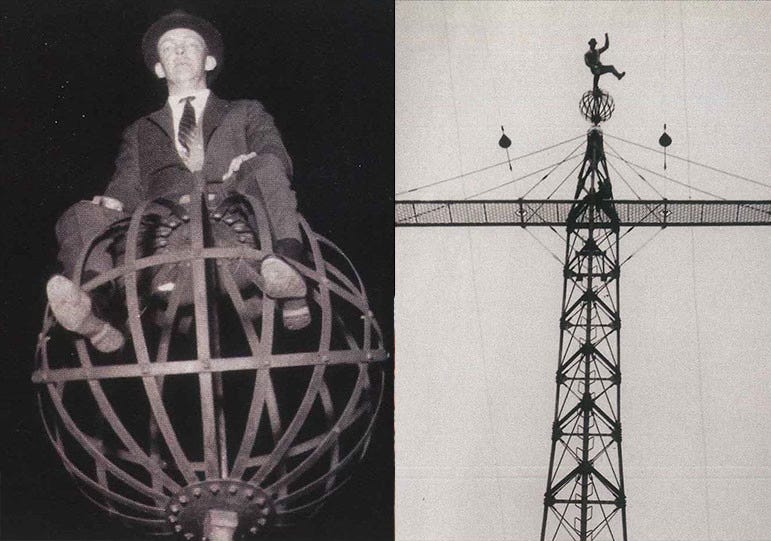

When FM was introduced, the FCC assigned a range of frequencies from 42-50 MHz, and Armstrong began experimental broadcasts from an elevated site overlooking the Hudson River near Alpine, New Jersey. In 1936, he built a 400-foot tower capable of sending signals as far away as New Haven and Baltimore. Photos from the period show Armstrong scaling the tower and perching at its top.

Seeking still further range, Armstrong accepted an invitation from his friend David Sarnoff to install an FM transmitter atop Manhattan's Empire State Building, at the time the tallest structure in the world and capable of transmitting FM signals as far as 100 miles.

Here is where things between Edwin Armstrong and David Sarnoff start getting dicey.

Sarnoff was interested in what FM could do, but also recognized what a threat the new technology presented to the foundations of RCA’s ethereal empire.

Sarnoff also had a larger fish to fry: television. By the time Armstrong got situated in the Empire State Building, David Sarnoff had spent something like $13-million – nearly $300-million in 2025 dollars – trying to engineer his company's way around the patents issued starting in 1930 to an obscure inventor in San Francisco, Philo T. Farnsworth.2

Patents not withstanding, Sarnoff was determined to be remembered as the man who delivered television unto the world. The last thing he needed was to foster a new radio technology at the same time he was trying to persuade the RCA Board of Directors that there was a payoff impending for all the money he'd spent on television.

Less than a year after inviting Armstrong to set up his FM transmitter at the Empire State Building, Sarnoff invited his old friend to pack up and take his gear elsewhere. Armstrong was evicted – but not before Sarnoff appropriated Armstrong's FM high-fidelity technology to transmit the audio portion of television programs – without any consideration for Armstrong's patents.

Lesson 3: But First, Let's Have A Little War

All of these new technologies – FM radio and television – went into a state of arrested development at the start of World War II. As soon as the war was over, gauntlets were thrown down.

RCA tried to introduce television at the New York World's Fair in the spring of 1939. This event is often heralded as the the beginning of commercial TV, but it was really little more than a publicity stunt Sarnoff staged to mollify his Board. At best it marked the beginning of another experimental phase, one in which consumers were allowed to participate so long as they ponied up $250-$600 ($5,000-$13,000 in 2025 dollars) for a 5" to 12" television console.

Worse, RCA was initiating this service before any kind of universal signal standards had been mandated. For television to be viable, there would have to be industry-wide agreement on such technical details as frame rates, lines-per-frame and, more importantly for this particular story, where within the electromagnetic spectrum television signals would be broadcast.

When Sarnoff introduced television at the World's Fair, RCA had settled on a 441-lines-per-frame video picture. But the industry already knew the technology was capable of considerably higher resolution.

Just before the war, the FCC adopted the NTSC signal standard,3 mandating 525 lines per frame – rendering useless any TVs purchased in 1939 and '40, and making that $200-$600 in 1939 dollars a high price to pay to be the first on your block.

Sarnoff probably welcomed the arrival of the war and with it an opportunity to start over. That let enough time elapse for people to forget how he'd jumped the gun in 1939. The war also afforded him the opportunity to command much of the Allies’ communications, a role that would earn him the sobriquet of "General" that his subordinates were obligated to call him for the rest of his life.

The war also set the stage for the brief appearance – and ultimate disappearance – of Channel 1.

Lesson 4: The Emperor's Priorities

Along with the 525-line standard, the NTSC established the Very High Frequency (VHF) band for the new service of television. Channels 1 through 13 were assigned to slots from 44-216 MHz. Channel 1 occupied 44–50 MHz, and a few experimental television stations did broadcast on Channel 1 in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

The adoption of standards left David Sarnoff with three priorities: First, he had to get television going. Second, he wanted to undermine FM in order to maintain RCA's domination in AM radio. And third, he had to use FM technology for the audio portion of television broadcasting.

Only this time, Edwin Armstrong was not willing to sell his patents for FM to RCA, as he had in 1920. And so begins one of the most underhanded and tragic chapters in American tech history.

The connection between the relocation of FM and the disappearance of Channel 1 is a tad convoluted, but within its folds lay hidden David Sarnoff's determination to impede the adoption of FM. And behind the-scenes, Sarnoff had a willing ally in the FCC.

The FCC had really messed things up in that 40-50 MHz range. At the same time that 42-50 MHz had been assigned to Armstrong's nascent FM enterprise, a portion of the same spectrum – 44-50 MHz – had also been assigned for TV Channel 1. If that wasn't confusing enough, an assortment of civilian mobile radio services like police, fire and taxi services were starting to use the same frequencies. Chaos reigned in the airwaves.

Before FM could render AM entirely obsolete, the newly anointed General Sarnoff joined forces with other major players in the industry to execute a a bit of tech jiu-jitsu: If they could get FM bumped into an entirely different bandwidth, the existing base of FM transmitters and receivers themselves became obsolete, evaporating countless millions of dollars in consumer and broadcaster capital.

Other services were indeed crowding that narrow slice of the spectrum, but FM was the only one with an installed base of transmitters and receivers, stations and listeners. There was no technical imperative to move it. Television had yet to start using the space, and the other services could just as easily have been relocated to other areas on the spectrum.

Nevertheless, in 1945 the FCC deigned to reassign FM to the 88-108 MHz range, where it is found on the dial to this day.4 That left the 44-50 MHz clear for its brief tenure as television’s Channel 1.

The dubious justification for the relocation was technical, but the motivation was pure corporate skulduggery. The only reason to relocate FM was because David Sarnoff wanted it moved, to extend the primacy of AM and to stall the adoption of FM while RCA maximized the ascent of television. This assertion is borne out in FCC Docket 6551, the proceedings that led to the spectrum reallocation in 1945 as well as internal documents that only came to light during litigation between RCA and Armstrong's estate that ran well into the 1960s.5

Epilogue: The Ghosts In the Phantom Channel

Even with FM out of the way, the other civilian services continued to infringe on the space that was supposed to be Channel 1.

Once FM had been banished from its native home, the FCC went on to assign the

Channel 1 portion of the spectrum that to the non-broadcast services that had also been using those frequencies. In 1948, Channel 1 was eliminated altogether, just as television antennas began shooting up all over the American landscape.

You can almost hear Nigel Tufnel saying "well... these start at two..."

Until it went entirely digital in 2009, the audio portion of analog television was transmitted using Frequency Modulation. Even as he tried to smother it in its crib, Sarnoff knew that FM was essential for TV to succeed free of the crackle and hum that plagued AM radio.

This fact was not lost on Edwin Armstrong, who spent the final years of his life in court, exhausting his fortune in litigation with RCA. Broke and broken, the man who liked to climb to the top of his own towering radio antennas stepped out of the window of his 13th floor Manhattan apartment on January 31, 1954. One of the most brilliant and accomplished inventors of the 20th century – a seminal figure in electronic communications – was dead at the age of 63, leaving his widow Marion to pursue his legacy for another decade.

RCA held out for another thirteen years, eventually settling with the Armstrong estate in 1967 to the tune of $1-million (~$10-million in 2025 dollars).6 Other electronics manufacturers quickly followed suit, effectively conceding they had used Armstrong's FM patents without proper licensing or payment for decades.

All these machinations in the 1940s set the evolution of FM radio back by at least twenty years. It was not until FM was adopted by the album-oriented rock radio format of the 1960s that the medium finally found its footing, and not until 1978 that the audience for FM exceeded AM.

This Tale of the Phantom of the Dial only scratches the surface of the decisions that confronted the broadcasting industry and its regulatory agencies in the years before and after World War II. All the legal, political and technical maneuvering over the spectrum in the 1940s resulted in what one writer described as “one of the major engineering botches of the century.”7

And the decision to consolidate television broadcasting into a narrow slice of just twelve VHF channels – rather than the far more abundant and suitable space in the Ultra High Frequency (UHF) range – assured the domination of a limited number of networks – RCA’s NBC, CBS, and ABC – for decades to come.

For now, at least, you know ‘the rest of the story’ behind the non-existent Channel 1, a sliver of bandwidth that bears the burden of a broad, internecine spectrum of history.

The next time you venture into an antique store and see an old TV, go ahead and amaze your friends with the strange, sad story of the dial starts at 2.

Or, you could…

And if you know somebody else who geeks out on this sorta stuff, then by all means…

"Hertz" are named for Heinrich Hertz (1857–1894) the German physicist who, in the late 1880s, provided the first conclusive proof of James Clerk Maxwell’s theory that electromagnetic waves could travel through space. In 1887–1888, Hertz generated and detected radio waves in a lab using spark-gap transmitters and loop antennas, proving they had the same properties as light. His experiments laid the groundwork for wireless communication, though he did not see practical applications himself.

Philo T. Farnsworth produced the first all-electronic video image in San Francisco on September 7, 1927. Every video screen on the planet can trace its origins to a sketch that Farnsworth drew for his high school science teacher in 1922, when he was all of 14 years old. As the Centennial of “the arrival of video on the planet” approaches in 2027, readers are encourage to find out more by reading The Boy Who Invented Television.

The 525-line, 30-frame standard, adopted by the NTSC in 1941, offered a significant improvement in image resolution and stability over the earlier 441-line format, and synced neatly with America’s 60 Hz power grid. The 525-line format remained the standard until the 1080-line HDTV was adopted in the late 1990s.

The decision to reassign FM ran counter to the FCC’s own Radio Technical Planning Board, which saw no compelling reason to for the reassignment.

See FCC Docket 6651 (1945); Tom Lewis, Empire of the Air pp 304-305; Lawrence Lessing, Sign-Off: The Life and Times of Edwin Howard Armstrong (1956).

There is another connection here between Armstrong’s case and Philo Farnsworth. After more than five years of litigation, RCA was forced in 1939 to capitulate to Farnsworth to the tune of $1-million, making Farnsworth the first independent inventor ever paid a royalty by RCA for the use of his patents. Seeing this result strengthened Armstrong’s resolve in his own litigation with RCA. David Sarnoff was equally determined that such a result would never happen again. Upon learning of his old friend’s suicide, Sarnoff insisted, “I did not kill Armstrong.”

Lessing, Lawrence, Man of High Fidelity: Edwin Howard Armstrong